East Prussia, Germany

Friday September 1, 1939,

I was awakened by my mother at about 4:30 a.m. with the words “Musst aufstehen, die Polacken schiessen” (you have to get up, the Polacks are shooting). As I had just turned 9, I didn’t understand what the fuss was all about. Prior to September 1, 1939, there had been some activity near the border. We lived about 1 kilometer from the border with Poland and had often crossed the border with our sleds in the wintertime. The sled run on the polish side was better than the one on “our side”. We played with the Polish kids often and the border patrol on either side never interfered.

But the last week in August 1939 things changed. A lot of soldiers with tanks etc. stationed themselves near the border. My mother forbade us to go near there.

Well it all came to a head early on this Friday, September 1st in 1939 [1]. The German army marched into Poland and almost ran over it. The first resistance was felt when they tried to cross the Weichsel (Vistula) river.

Things became a little confused in our house. My father, after listening to the radio, took his bicycle and went to the border. By that time the German army had already “Liberated” that part of Poland and my father was well known, so he crossed into the village of Johannisdorf where many of his boyhood friends lived. The reason he knew so many people in Johannisdorf was that this village, along with 4 others, were given to Poland after Germany’s defeat after World War one (from 1914 to 1918). Poland wanted access to the Baltic Sea and a corridor, dividing East Prussia where we lived, with the rest of Germany was created. My mother gave my brother Helmut strict instructions to keep an eye on me and Manfred. Helmut was almost 15, I had just turned 9 and Manfred was 4 years old. Somehow Helmut disappeared and since my mother was busy looking after my aunt (Tante Idchen), the house and farm, I took Manfred and we also went to the border. I remember seeing broken border barriers and vacant houses.

I can’t remember what I thought about all that; but somehow I felt uneasy and I took Manfred home. I really don’t know if my mother knew where we had been.

Our radio was on all morning. My mother was concerned about her parents and Tante Olga who lived near Danzig. When we heard a big explosion the radio announced that the Poles had blown up the major bridge over the Vistula river and that fighting was occurring near Danzig.

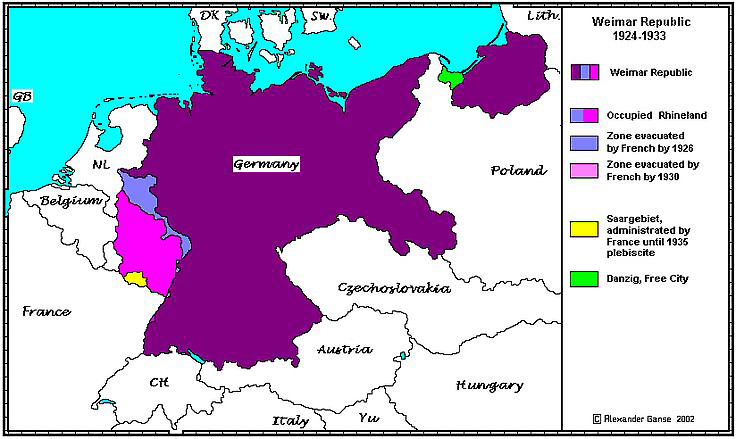

After the First World War when Germany was divided, Danzig became a “Free State”. I really don’t know how it all worked. Linda, if you can find a map of Europe which gives you the borders prior to 1939 maybe you can get a clearer picture.

We lived in Mewischfelde near Marienwerder (east of the Vistula river). Dirschau (I don’t know the Polish name [2] ) is where the big bridge was blown up. The rest of the day and how the war started is a complete blank in my mind.

England and France declared war on Germany on September the 3rd in 1939. Bits and pieces of adult conversations left me with the thought that bad times were ahead. But as a 9 year old child one isn’t disturbed by these things. If I recall, Poland surrendered after 21 days.

Our life went on as usual. Rations were introduced but didn’t give us any hardship. The young men from the village were called in to serve the “Führer” and the older farmers had to help out where the wife was left alone to run the farm. In September 1941 I started what was called “Mittelschule”. After 4 years of Elementary School one could go either to Mittelschule or Oberschule. Since I, at the ripe age of 11, considered the Oberschule snobbish, I pestered my father, whom I could and did wrap around my little finger, to let me go to the Mittelschule.

I had to take the train into town 6 days a week (yes, we had to go to school on Saturdays as well). I liked my new found freedom. Now I was a “Big-shot”; taking the train by myself, running errands for my father who was mayor of our village. In November 1942 my brother Helmut turned 18 and was promptly called into the army. He received his basic training in Wuppertal near the Rhine River and after about 3 months was shipped out to Russia; or should I say “to the Russian front”.

Hitler in his “infinite wisdom” had invaded France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark and Norway. I can’t recall dates; but these things can be found in libraries.

Life during the war

Mail from Helmut was sparse and I detected that my parents were worried about him and the outcome of the war. On June 22 (I don’t remember the year) the German army marched into Russia [3]. It was a Sunday and when the news came over the radio; I remember my mother saying “Jetzt haben wir den Krieg verloren” (now we lost the war). My father became upset and told her never, never to say anything like that again. He might have agreed with her; but under Hitler’s regime a comment like my mother made was considered a crime.

Other than having to do without some things we didn’t feel any effects from the war. We lived on a farm where we grew our own veggies, fruits and animals. The things that were rationed could always be obtained for a pound of butter or some meat. Naturally these things had to be done secretly. My father who was mayor of our village and also held a post in the Nazi party could not afford to do anything illegal; so I became my mother’s “partner- in- crime”.

The ration-coupons were distributed by the mayor (it was actually my mother who did that) and a few extras found their way into our pockets. I had to go to the county seat to pick up the package with all the coupons once a month and when we checked the list the count was never right. Not to arouse suspicion some were returned. Since as farmers we were not entitled to any dairy meat or bread coupons; but I always had one of each of these for my own use to get a piece of cake or an ice-cream.

Many years later, actually it was on one of my visits to Niedernstöcken from Canada, we told my father about it. He was appalled at the risk my mother had taken.

The days went by rather uneventfully. Some stand out in my mind. Christmas Day 1943 is one of them. Helmut, who was fighting on the Russian front hadn’t written for a long time and a general gloom had settled over our house. The traditional Christmas tree was forfeited, we used the advent wreath as a symbol of Christmas. On Christmas Day friends had been visiting us and stayed for “Abendbrot”. They had just left when the last train from town went by. The engineer tooted his whistle a few times when he passed our house. We thought he wished us a good Christmas. The train was a narrow-gauge railroad and we knew the engineer, conductor and all the people on it. About 5 minutes later we heard footsteps nearing our door. My father went to see who it was and…Helmut stood at the door. The dog, who normally announced every visitor, didn’t bark but was as happy as all of us. I can’t describe the way I felt, thinking about that evening so many years later, still chokes me up.

After a good wash (Helmut only, we didn’t have a shower or bathroom) and an enormous meal the family settled down. The next morning my father, Helmut, Manfred and I went to cut a Christmas tree. I do remember that tree very well; it was a beautiful blue spruce and took up a large section of our rather small living room. As I am writing this, I forgot to mention that just as Helmut walked into the door, I had started to write a letter to him. Helmut stayed for 2 weeks and the “goodbye” was hard on everybody. Life went on…

War is coming to East Prussia

Then in the summer, 1944 (I can’t remember the exact date) I came home from school to find Tante Idchen sitting on the couch crying, my mother near her, also crying and my father standing at the window. My first thought was that Helmut had been killed. But my aunt looked at me and pointed to a letter which lay beside her. It had been written by a nurse from an army hospital in East Prussia (Gumbinnen was the name of the town) where Helmut was a patient. She said in the letter that both eyes were injured, one worse than the other. After talking to some friends who offered to keep an eye on us, my parents went to visit him.

To leave us with my crippled aunt and only polish workers was a bit risky but it all worked out well. My parents returned and told us that Helmut had lost one eye. He was transferred to another hospital in September of the same year. This one was located in Leslau (Lipno in polish), My mother and her sister (Tante Mariechen) went to visit him there. My father pulled a few strings and Helmut was transferred to a hospital in Marienwerder (our nearest town) as an outpatient. He had to report to the hospital once every week. Everybody was happy that he was OK and home.

We celebrated his 20th birthday on November 17, 1944 with a real party. Christmas came and went. But somehow I felt that all the adults were a bit uneasy.

On or around January 12, 1945 the Russian army started their big offensive push and within days advanced more and more near the original German borders. My father’s birthday on January 19/45 was a very subdued gathering. We could hear the cannons etc. in the distance. Helmut, who had gone to Marienwerder for his weekly report to the hospital called (yes, we had a telephone. Our number was Marienwerder 2172). The doctors wouldn’t let him come home. The entire hospital was being evacuated to Halberstadt near the Harz mountains. I had to take the train into town to bring him clothes etc. When I walked from the train station to the hospital, as there was no public transportation in Marienwerder, I saw many, many “Fluchtlinge”.

A Fluchtlinge is a person who had to flee; that is where the word “Die Flucht” comes from. Die Flucht means “the fleeing”.

The Fluchtlinge I saw came from Lithuania, Estonia, Lettland and East Prussia. They were all in covered wagons – an awful sight. When I related what I had seen to my parents, they had a very worried look on their faces.

Räumungsbefehl

School didn’t start, as usual, after the Christmas holidays; all available buildings were used for Feldlazarette (field hospitals). My father received instructions to contact the mayor of a village a few miles west of us for evacuation. I guess Hitler or his generals had intended to hold the advancing Russian army at the Weichsel (Vistula) River. Our village teacher was dispatched to check out the details. Upon his return he was very, very upset. The other mayor didn’t know anything about all of Mewischfelde (our village) coming there. I do recall part of the conversation he had with my father. One sentence sticks in my mind: “My wife and children are not going there, I would rather kill them”. The day after his birthday, November 20, my father received a highly confidential document. It was called “Räumungsbefehl”. It translates loosely into “clearing out orders”.

We had to burn all Nazi paraphernalia and many, many baskets full of documents, books, etc. We had a real bonfire.

All during the war we had polish helpers on the farm and in the house. These people came from the occupied sections of Poland and the Ukraine and were more or less forced to work. We always had 2 girls and 1 guy working for us. The guy, his name was “Benneck”, had to help carry everything to the fire. I do remember the smirk he had on his face. The 2 girls we had at that time were called Janina and Katchka.

The Räumungsbefehl stated that my father would receive a code word plus a number, which would mean – everybody from the village had to be evacuated so and so many hours after the word was received. I have tried, but cannot remember the code word and number.

Even though this whole thing was highly confidential my father talked about it with my mother and aunt and my big ears picked it up. Our wagon was more or less ready; provisions were packed; the horses readied etc. On Sunday evening January 21 in 1945 my father received the code word. He went to notify the teacher and a few other people who in turn had to notify their neighbours etc. My mother stayed on the phone. The atmosphere in our house was total gloom. My father’s sister, Tante Idchen, who lived with us prayed and cried. She was totally crippled by arthritis and completely helpless. I cannot recall-how I felt at that time; but sensed not to bother anybody and stay quiet. Then the phone rang; it was our postmistress Frau Dalley.

She screamed into the phone something like: “Frau Funk, mein Gott, mein Gott!” My mother tried to calm her down saying: “Beruhigen Sie sich doch, Frau Dalley, wir sind doch noch alle hier!” (Calm yourself, we are all still here). Frau Dalley finally calmed down and told us the horrible news that our teacher had shot and killed his 2 children and himself. His wife, whom he also had wanted to kill, ran away to the post office. That was a big shock to all of us. My father hadn’t returned from alerting the rest of the village so I had to get on another bike (no cars in those days) trying to find him. I remember pedalling like hell, slipping on icy paths and crying; but I found him.

Monday, January 22, 1945 we left with only a wagon load. When my father carried my aunt out of the house to the wagon, one of her canes knocked over a vase. When it shattered into 1,000 pieces she said; “Vielleicht bringen uns die Scherben Glück”, (Maybe the shards will bring us luck).

We joined hundreds of other people, some from our village, others from neighbouring villages. Since it was January, the roads were very icy, many wagons simply toppled over, others broke down and people left the few belongings they had taken, behind.

I decided to walk beside our wagon. Often we were stalled or stopped due to mishap or attacks by Russian low flying planes. The first day we only made it to a boyhood friend of my father’s maybe 20 miles or so away from Mewischfelde. One could hear the cannons constantly and the sky turned red from the distant fires.

We went on the next day and the day after that. Our destination was Osterwick near Danzig to my mother’s parents’ house. When we, with our next door neighbours, named Janzen, pulled up to the house in Osterwick my grandfather had just died about 10 minutes earlier. Needless to say my mother was upset but glad that he didn’t have to see us in the poor state we were in. The ground was frozen, so it took many men many hours to dig a grave for my grandfather. They couldn’t even get a-proper coffin; he was buried in a plain pine box.

We stayed in Osterwick til just past Easter. The roar of the cannons became louder and louder. The horror stories about rape and murder became more gruesome. Tante Idchen begged my father often to shoot her. It simply was an awful time. Easter Sunday April 1945 sticks in my mind. My mother told me that she and my father had talked about shooting us all rather than being captured by the Russians. I told her if my father would do that, Helmut would be left alone in the world without a family. I really don’t know if I believed what I said or only used it as an excuse to live. I shared a bed with Tante Olga. Sleep was something I got little of; my father walked the floor at night and I was scared that he would kill us all. I think that particular incident made me afraid of guns for the rest of my life.

We realized that we were completely surrounded by the “enemy”. The Russians pushing from the East and the allied forces pushing from the West, a real hopeless situation [4]. Well, we loaded the wagon again, and again together with our neighbours went on. This time to a place called Danzig-Neufähr (that was where Tante Lieschen lived; another sister of my fathers). My mother must have been torn into two; as we left Tante Olga, my old grandmother and Tante Ilse with 4 young children and pregnant with #5 there. Tante Ilse is my mother’s sister-in-law. (She is the mother of Helga Kahle in Niedernstöcken).

When we arrived at Tante Lieschen’s house – more chaos. The roar or the cannon much closer again, nightly bombing by Russian planes. My father, who decided to do a noble deed, volunteered to “save the Fatherland”. I can’t remember what date it was but one night the bombing was particularly severe. We were all sitting in the cellar. When the bombings were over we heard footsteps above us; my mother recognized them as my father’s. We emerged from the basement to a scene of total destruction. Debris, bomb craters, dead horses everywhere. Tante Lieschen and her husband Onkel Albert Saemann had decided not to leave their house and urged my mother to take Manfred and I and just run for our lives. They would keep Tante Idchen there. Saying goodbye to Tante Idchen was the hardest thing I ever had to do in my entire life. My father walked a short distance with us and we said goodbye to him. I can still see it all very clearly. It was just getting light, my parents looking at each other. My father, who wore his revolver in a holster, looked at us again, my mother putting her hand on the holster, nodding her head. Nothing happened – we parted and the 3 of us trudged on and my father went back to his duty.

We walked, I really don’t know how far or how long; but we arrived at my mother’s aunt’s house. That is where we met Tante Olga, Oma and Tante Ilse with her children (Helga, Jürgen, Anneliese and Ingrid). There were also more relatives of my mother’s there. Low flying planes dropped bombs day and night. When one bomb hit the house it was decided to move on. We got a wagon (I don’t know from whom), loaded Oma, Tante Olga and our neighbours and went on. Two of my mother’s cousins with their families followed. I still walked beside the wagon, too scared to ride in it.

Somebody ahead of us mentioned that 2 soldiers (German) had been hung on trees with a sign around their necks saying: “This is what will happen to all who desert the Fatherland in time of need”… My mother insisted that I walk on the other side of the wagon. She wanted to spare me that ugly sight. Except there were 3 dead German soldiers on that side.

We parked our wagons (3 all together) under a clump of trees near a farm house. It was almost safer to be outside than inside a building. The bullets were already flying over our heads; the fighting very close by. The son of my mother’s cousin who had had a tumour removed from inside his head as a teenager years ago was unable to serve in the army. He took a gun, walked behind our wagon and killed himself.

Again – these damn guns!

Operation Hannibal

Well, we couldn’t stay there any longer. Rumours, I don’t know who told us about it, spread that ships were being loaded near Gotenhafen (Gdynia in Polish) and people would be taken to then occupied Denmark [5]. Well, off we went; we were 3 wagons all together. The horses were tired, the road bad and clogged, therefore the going was very slow. We went to another cousin of my mother’s and parked again away from the house under some trees. We were all infested with body and head lice, always slept in our clothes and were constantly afraid· We met an old man named Schultz; his family had all been killed by a bomb some weeks earlier. He became our “Kutscher” (the guy who looked after the horses). One day my mother walked with him to the barn where the horses were kept. They were standing in a doorway; suddenly a bomb dropped; a fragment hit and killed Herr Schultz.

I went with Manfred into the village to get a warm meal. The army had set up some sort of a soup kitchen. While standing in line, 2 men came up to me and called my name “Elschen Funk”. When I looked up I recognized them as 2 farmers from our village Mewischfelde. They were looking for their families. Since they were in uniform and had a jeep they drove me and Manfred and our Erbsensuppe (pea soup) back to the wagon. They told us to get quickly to a place called Einlage; the last boat going to Denmark would be leaving the next day.

Well, off we went. We took what we could carry and boarded a small trawler which took us out to sea to be transferred to a big ship. It was all very frightening. We had to climb a rope ladder to the deck. Manfred was so scared and is to this day afraid of boats and water. We were ushered into a huge room with countless other people. Tante Olga and Oma were also there. My grandmother was dying – but no help. Finally the boat left, shooting, bombs etc. all around us. We were in sort of a convoy with 2 other refugee ships – each loaded with about 7,000 people. Our ship “Die Kronenfels” developed engine trouble and stopped on the ocean for a little while. The ship behind us overtook us and while still in easy view hit a mine and sank [6]. I happened to be on deck and heard the screams of the drowning people. About 50-60 were rescued and brought aboard. Dates seem to be blurry; but I do believe that we docked in Copenhagen on or around April 19, 1945.

Then on to trains. We had to leave Oma and Tante Olga behind. The German soldiers told us Just to move along as we would all be taken to the same place. Oma had died just as we docked. Her body was probably dumped into the sea. (the sea I am referring to is the Baltic Sea). So we found ourselves on a train. We consisted of my mother, Manfred, I, our neighbour from ‘back home’ Frau Jantzen with her 2 children Gunter and Margot. Apparently some train tracks had been sabotaged or mined, the danger of our train derailing or exploding was always there. I cannot remember if or what we ate. On April 22, 1945 we arrived on the isle of Jütland (the western isle of Denmark). Look it up on a map. Our final stop was a town called Esbjerk. From there into army trucks and after a few hours arrived in Oksbøl [7].

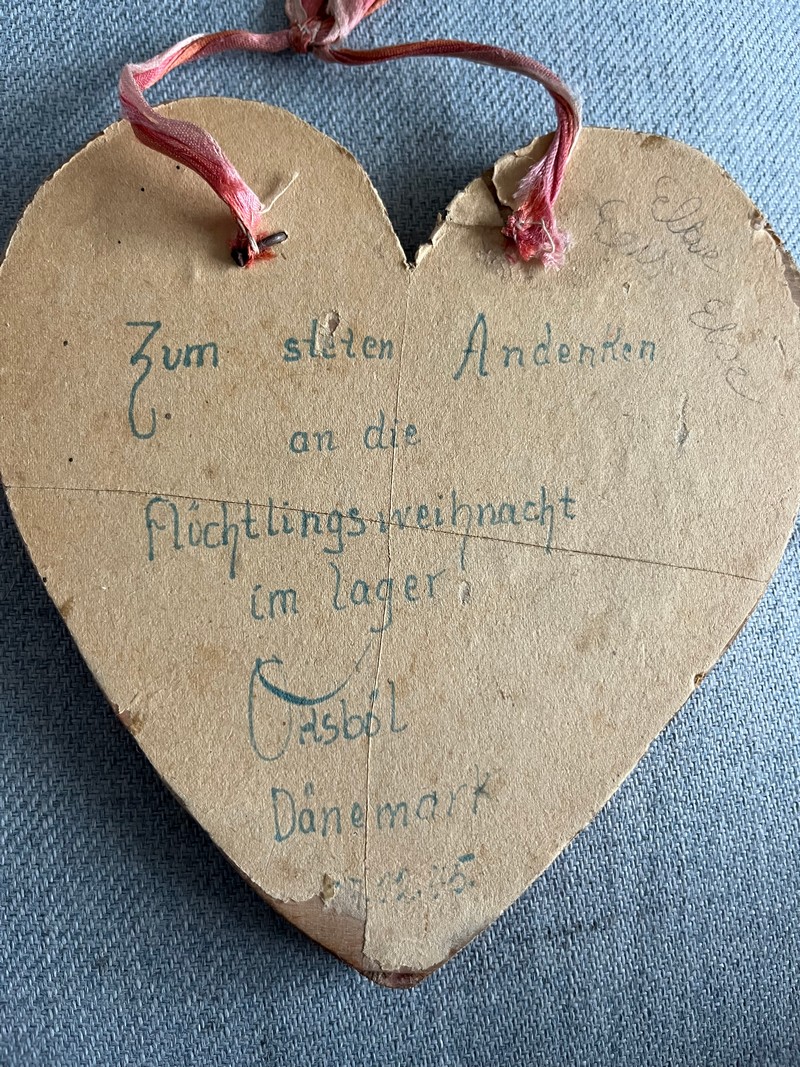

Refugee camp in Oksbøl, Denmark

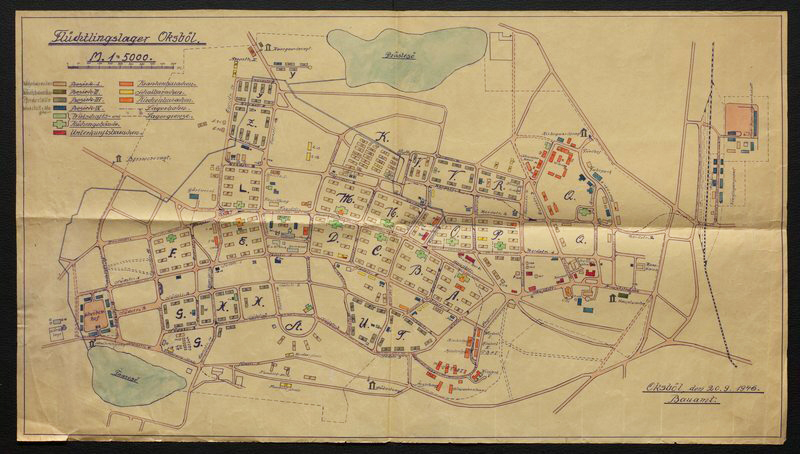

Oksbøl used to be an army recruiting camp for the Germans. It was situated in a large forest; about 100 barracks and a few barns for horses, a public bath house, a large arena type building which served as the theatre, movie house and church. We were put into a barrack in the E block #7 room 6. Each room had 7 bunk beds, 3-4 small drawer-sized lockers, 1 large table and a bunch of Hockers (stools). We shared the room with our neighbour Frau Janzen and her 2 children, my mother’s cousin Tante Greta Hannemann, her husband Edward Hannemann, their 2 daughters Erika and Hannelore, the wife of another of my mother’s cousin Tante Frieda Schmidt, her 3 children, Gertraud, Helmut anti Erhard and Frau Schumacher with her daughter Lisa. Frau Schumacher came from East Prussia and was only the wife of a farm labourer. But she turned out to be a real friend and my mother is still in touch with her. You have to remember, Linda, that I grew up where a “class system” existed, I never liked it and neither did my mother; but my rather was all for it.

My mother was ill when we arrived in Oksbøl; she stayed in bed for about 2 weeks with high fever and no medicine. I took care of Manfred as best as I knew how. Food was provided for us from a large army kitchen. We had to walk up there with whatever containers we had to pick up the slop. It really was awful stuff. No salt, no meat – it looked like barf. But we were hungry and ate it. In the morning tea was served in the same way and a few slices of mouldy bread.

As time went by things became a little better organized. Other rations, like margarine, jam, bread and milk for the young children were distributed by a foreman for each barrack. The women were assigned to kitchen duty to peel potatoes, carrots, slice cabbage etc. It was a treat for us to have a piece of raw cabbage or raw carrot. Once the war ended and the German troops withdrew we were subjected to sudden police raids by the Danish military police. They took everything of value away. My mother had a gold pocket watch with her. Manfred wore it day and night around his neck as children were not so thoroughly searched. We did not have any sheets or pillows; only 2 very scratchy army blankets each. We had lice and there were bed bugs everywhere. A delousing schedule was organized. We weren’t sure it wasn’t a gas chamber they herded us into. It really wasn’t very pleasant. But thinking back on that time so many years later; it changed me from a spoiled brat to what I am now.

I learned quickly that my mother needed all the support she could get to stop her from going crazy. She had gone through a lot in those last 3 months, and would often just sit and stare into space. But as time went by she became resigned to the situation.

I had heard about a school so Erika Hannemann and I went to investigate. Well, we found that one barrack was the schoolhouse. We both enrolled and stayed until I graduated from it in the summer of 1947. Erika dropped out.

There was no mail; therefore we didn’t know if my father or Helmut were still alive or their whereabouts. A library left over from the German army gave us a bit of a diversion. A weekly movie was shown, church services were held etc. There were about 20,000 people in that camp. It was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with armed guards patrolling on the outside. A hospital was established, a cemetery created etc. The camp itself became like a town except there weren’t any stores and nobody was supposed to have any valuables or money. I didn’t have any shoes for about a year. The ones I had worn leaving home were too small so Manfred wore them.

Naturally they were far too big on him. The few clothes we had were darned and patched and patched again. Since we all looked shabby it really didn’t matter. I believe that I came out of that being a better person; but Manfred still bears the scars.

One incident which happened on January 20, 1946 is worth mentioning. Does one believe in ghosts? It had been my father’s birthday on Jan. 19 and we had talked about him and previous birthdays. That is the reason my mother remembered the date so well. Since we slept in bunk beds; I had the top bunk – my mother awoke during the night to see something white rise itself to my bunk; remain there for a few minutes and then disappear again. At that exact hour my very favourite aunt Tante Idchen had died. We found that out much later through letters from Tante Lieschen whom we left Tante Idchen with. Even now, more than 40 years later, I still cry just thinking about the horrible death she had. She was taken from a railroad car, put in freezing temperatures on the platform and left there to freeze to death. She was the most; loving and selfless person I have ever known. Where was God when she had to suffer so much?

But that is another story.

Former soldiers (Germans) were transported back-to Germany around July 1946. My mother gave the address of my uncle Eduard (my father’s youngest brother) who lived in Berlin to a soldier. He contacted my uncle and he in turn contacted my father. Once the mail started coming, Frau Janzen received a letter from her husband -saying; “Jetzt bin Ich mit Otto bei Tante Guschul in Westfalen” (Now I am with Otto, my father, at Tante Guschel’s in Westfalen). At least now we knew my father was alive. Shortly afterwards we also received a letter from my father. He had found Helmut who had gone to Niedernstöcken where his regiment had spent a few weeks recuperating from heavy fighting and casualties during the war. At least we were all alive.

By the summer of 1946 when I had graduated from school, I decided to apply for an “office job” right in the camp. The red cross had set up an office finding lost families etc. I thought I could prepare myself for a job somewhere in Germany once we were allowed to return, We received extra rations for working; these came in very handy as Manfred looked like death warmed over.

From our office plans were made to slowly return all people from Denmark back to Germany. The first group who had relatives in Hannover-Braunschweig left in September 1946. The next group was supposed to leave right after. This group was supposed to go to Westfalen – Rheinland. Since my father was there, we belonged to that group.

But for some reason it all stopped. Naturally my mother was very disappointed. Then a new plan came into operation. Relatives of wounded soldiers now residing in Hannover-Braunschweig could leave. I took a letter Helmut had written and a picture he had sent us to my boss and we were put on the list.

Back to Germany

Finally on November 12, 1947 we were notified that we could leave. My mother had found an old family friend who had made a trunk for us to pack our meager belongings. It was taken away from her at the checkpoint; they claimed the boards it was made of came from Danish trees. She was given 2 paper sacks to put our stuff in. Well, finally we were-marched along the main road of the camp through the barrier to the village train depot. We boarded the train and went south (look on the map). I can’t remember much about that train ride.

We were unloaded near the German border. The barrier on the Danish side opened and we moved single-file into the no-man’s land. When everyone was through the Danish barrier it was closed again and the one on the German side opened. Everybody simply ran across it.

I remember a mother-daughter pair kissing the ground. Now we were put into English army trucks and brought to Hamburg’s main train station. The damage caused by much heavy bombing was still very evident. The train which took us to Celle finally arrived and was badly overcrowded. I carried my featherbed (the only one we had saved) in a sort of back-pack on my back. My mother got on the train first, then l pushed Manfred in and almost didn’t get in myself but somebody gave me a good push and I squeezed into the overcrowded compartment. We had no money, no food and I can’t remember if we were given food on that train or not.

Finally we arrived in Celle. No train leaving from there until the next morning. My mother went to try to telephone Helmut or my father in Niedernstöcken and left me in charge of Manfred and our belongings. When she returned after having spoken to Helmut she found Manfred and I sleeping on our baggage but nothing was missing. The train station was filled with chaotic people everywhere. Finally it was morning and we boarded the train for Schwarmstedt. There we were met by a cousin of Lisa’s. She recognized us immediately, probably by our shabby clothing.

Neither my father nor Helmut could get the day off from where they worked to come and meet us. Annie Oberdieck who later married Gerd Schierkolk in Niedernstöcken (she is Lisa’s cousin who met us in Schwarmstedt) took us to another relative for a few hours until the bus left for Niedernstöcken. There we ate our first real meal. Then on to the bus. When we got off the bus in Niedernstöcken at the Kreuzung (crossroad) we didn’t know which way to go and asked. We were heading to Bodes where Helmut worked and lived.

Finally we were there. November 13, 1947. Helmut had refused to celebrate his birthday which was on the previous day; he wanted to wait for us.

My father who worked for another farmer by the name of Goers (behind the church) didn’t even get the time off to say hello, he had to wait till after supper. No wonder hard feelings remained between the locals and some Fluchtlinge (refugees).

Maybe at a later date I can and will continue with our life in Niedernstöcken.

Else Wilke (Funk) December, 1987.

The author

This memoir was written by Else Clara Wilke (born Funk) in 1987 as a birthday gift to her daughter Linda whom she is addressing in her article.

Else and her family resettled in the village of Niedernstocken outside of Hannover in November, 1948 in what was now West Germany. There she met her future husband, Horst (also a newly resettled refugee). They and their 2 children (Angela and Marion) immigrated to Canada in 1953. They lived in Ontario until their retirement to the beach in Mexico in 1986.

After Horst‘s death in 1990, Else moved back to Canada until her death in 2023.

Footnotes

- 1 September 1939 is remembered as the day the Second World War began. Early that morning, Germany launched a coordinated military assault on Poland, employing the fast-moving Blitzkrieg strategy that combined aerial bombardment, armored divisions, and rapid infantry advances. The attack followed a period of rising tensions in Europe, including the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, in which Germany and the Soviet Union secretly agreed to divide Poland between them.

. - After World War II, Poland took over former eastern German territories such as Silesia, Pomerania, and East Brandenburg, they were placed under Polish administration following the Potsdam Conference (1945). To integrate these regions, authorities launched a large-scale program to rename towns from German to Polish. Whenever possible, historical Slavic names were restored; otherwise, new Polish names were created. The Commission for the Determination of Place Names oversaw the process. Major changes included Breslau → Wrocław, Stettin → Szczecin, Danzig → Gdańsk, and Oppeln → Opole, completing the map’s Polonization.

. - Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941.

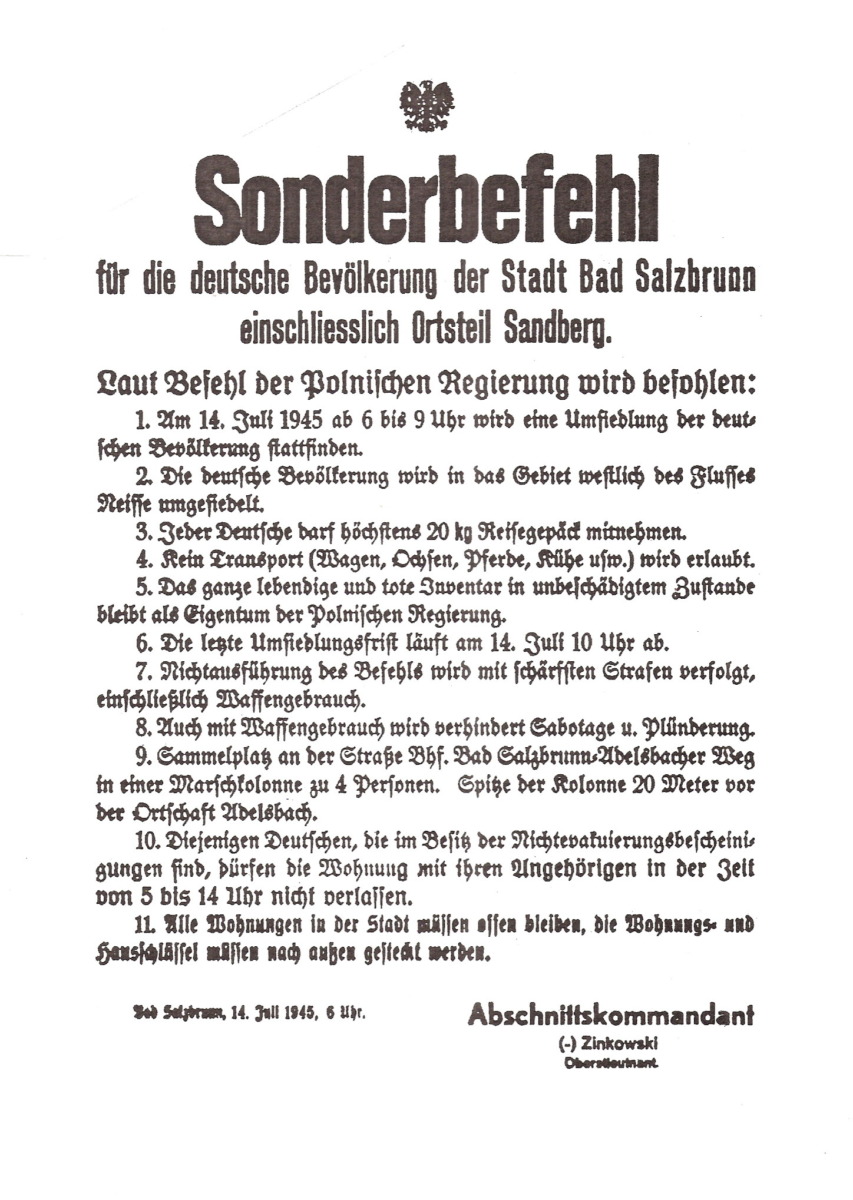

. - The flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950) was one of the largest forced migrations in European history, involving more than 12 million people. As the Red Army advanced into East Prussia, Silesia, Pomerania, and other eastern territories of the German Reich in late 1944 and early 1945, millions of civilians fled westward in harsh winter conditions. Many traveled by foot, horse carts, or overcrowded ships during Operation Hannibal, facing bombings, hunger, disease, and freezing temperatures. Countless lives were lost during these chaotic evacuations.After Germany’s defeat in May 1945, the Potsdam Conference authorized the “orderly and humane” transfer of German populations from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

In practice, however, expulsions were often brutal. Germans were forced from their homes, placed in camps, or marched to collection points before being transported into the occupation zones of postwar Germany. Property was confiscated, and many suffered violence, malnutrition, and illness. By 1950, West Germany and East Germany had absorbed millions of expellees and refugees, reshaping demographics, politics, and society. Today it is recognized as a major humanitarian tragedy linked to the wider devastation of World War II.

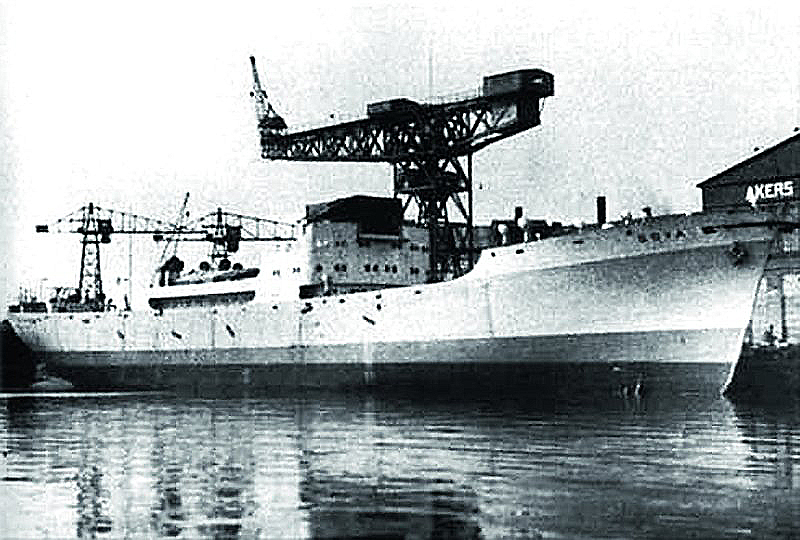

. - Operation Hannibal, launched by Germany in January 1945, was one of the largest maritime evacuation operations in history. As the Red Army advanced into East Prussia, Pomerania, and West Prussia, millions of German civilians, wounded soldiers, and military personnel sought escape across the Baltic Sea to safer areas such as Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark. The Kriegsmarine mobilized hundreds of vessels—warships, merchant ships, fishing boats, and passenger liners—to transport refugees under constant threat from Soviet submarines, aircraft, and ice-filled waters.

The operation continued until May 1945 and evacuated an estimated one to two million people, though numbers vary. Despite its scale, the operation is also remembered for several catastrophic sinkings, including the Wilhelm Gustloff, Goya, and Steuben, which resulted in massive loss of life.

. - The MV Goya (motor vessel) was a Norwegian-built freighter that was repurposed by Germany during the final months of World War II. In April 1945, she participated in Operation Hannibal, a massive German evacuation that sought to transport refugees, wounded soldiers, and civilians across the Baltic Sea. On 16 April 1945, Goya left the port of Hel in a small convoy. The convoy included Kronenfels, a Hansa-type cargo ship, and the steam tug Ägir, escorted by two minesweepers (M-256 and M-328). However, Kronenfels developed engine problems early in the voyage, forcing the convoy to stop for about 20 minutes for repairs.Later that night, the Soviet submarine L-3 detected the convoy north of Cape Rozewie. At around 23:56, L-3 fired four torpedoes; two hit the Goya, one amidships and one in the stern.

The explosions were catastrophic — the Goya broke in two, burst into flames, and sank in just a few minutes. Because of the Kronenfels’s engine trouble, the convoy was moving slower than it otherwise would have — likely contributing to its vulnerability. Der Spiegel Thousands of people were on Goya (estimates go up to 7,000), and only a few hundred survived. The disaster is considered one of the worst single-ship maritime tragedies in history, exceeded only by the January 1945 sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff.

. - The Oksbøl refugee camp in Denmark was one of the largest camps for German civilians after World War II. Established in 1945, it housed up to 35,000 German refugees who had fled the eastern territories as the war ended. The camp operated like a small, closed city with its own hospital, school, shops, and even cultural activities. Conditions were strict, with limited contact between refugees and Danes. More on the Oksbøl refugee camp in this link.

Sources

- Stiftung Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung

- Danmarkshistorien

- Wikipedia – Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

- LandmarkScout – The largest refugee camp in Denmark – Oksbøl Varde Denmark

- Warfare History Network

- Bundesarchiv

Thanks so much for all your work and for publishing mom’s story with all the extras.

Is there a way to translate it into German?

Hi Linda, thank you for your question. I used Google Translate to translate it. I’ve sent you a copy by email. Best regards, Patrick

Thank you, a very, very interesting article. Some members of my extended family had to make this escape from the russians, and left East Prussia by ship during Operation Hannibal.